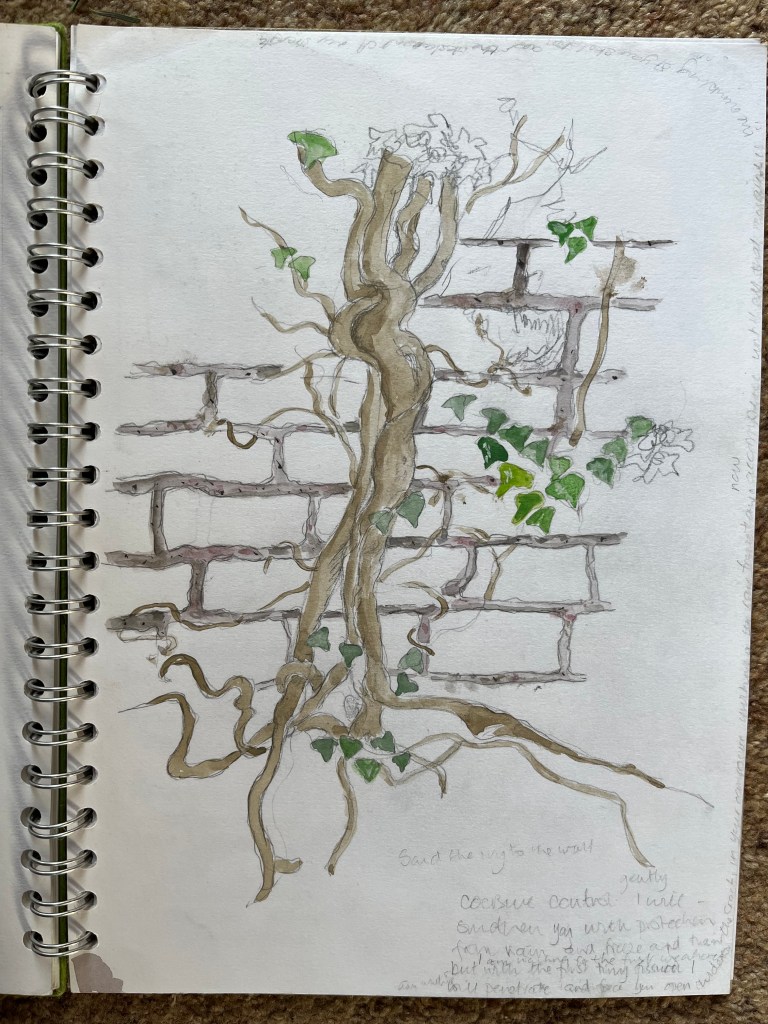

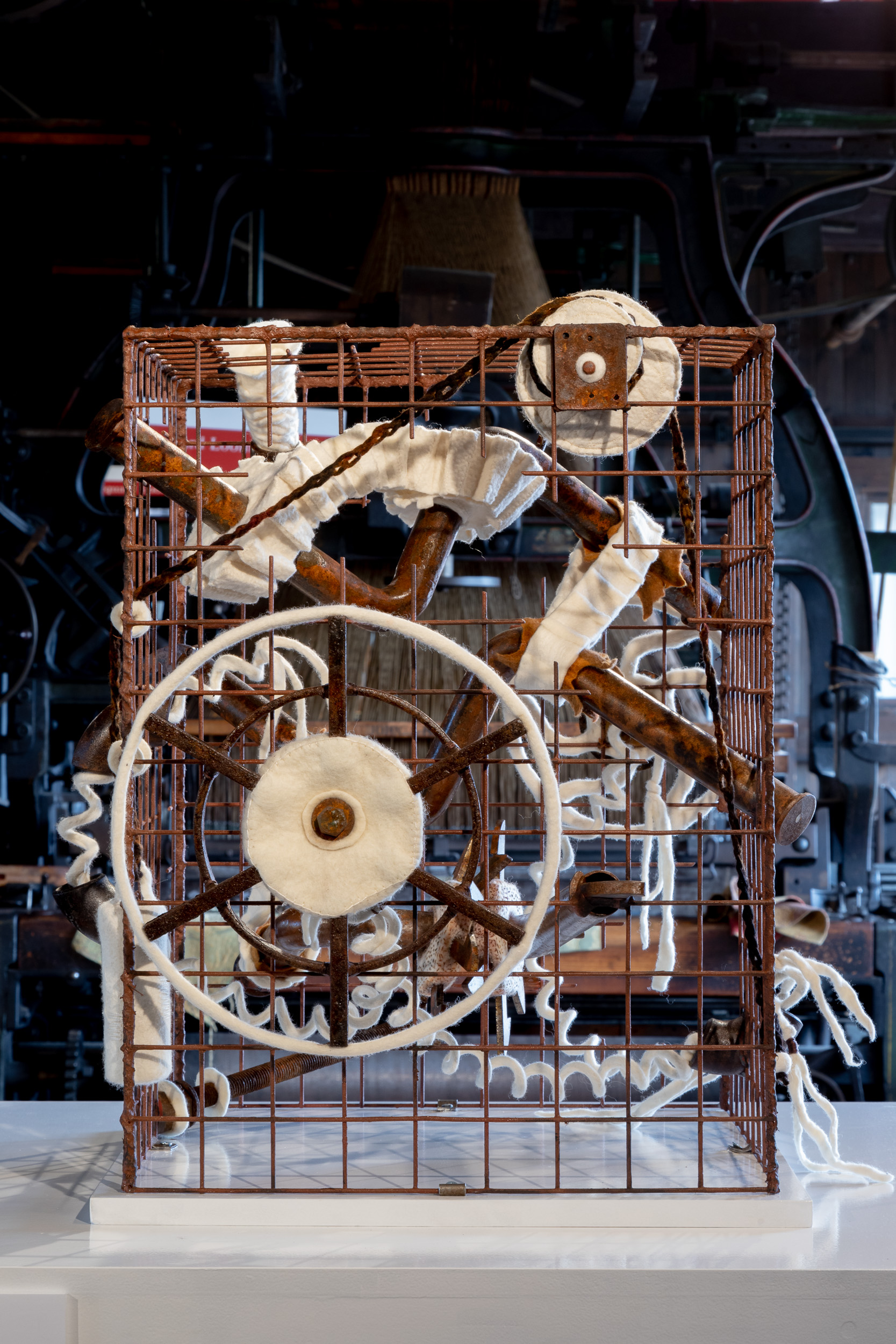

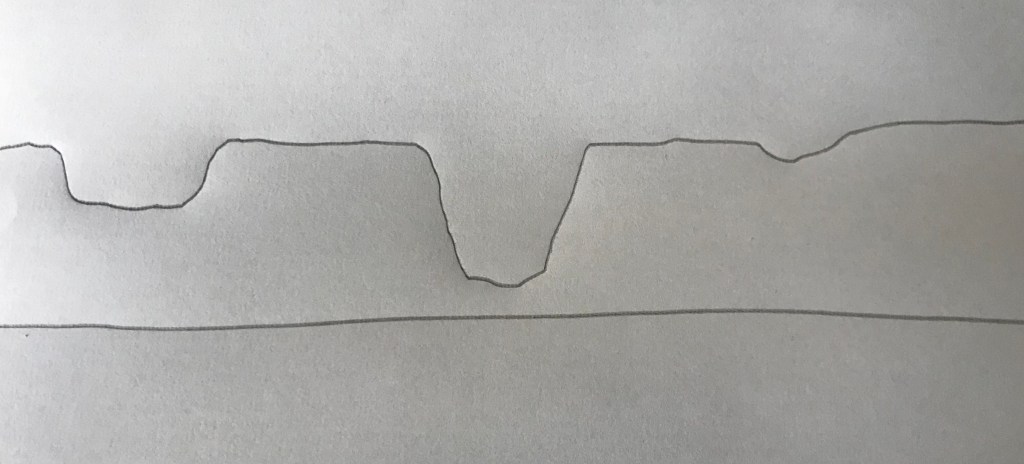

There is a section of wall overlooking fields towards Crofton which is a favourite with walkers at bluebell time. A hole in the wall provides a perfect frame for the bluebells growing inside the estate. The first of these photos was taken in about 2016, I think, and the second a year later and the third is as the wall was in 2021. The rapid decline from hole to gap is alarming and as the wall’s defences are broken and water can get in more easily, it will continue apace. I wanted the work I made in response to this to show the passage of time – so a triptych seemed appropriate.

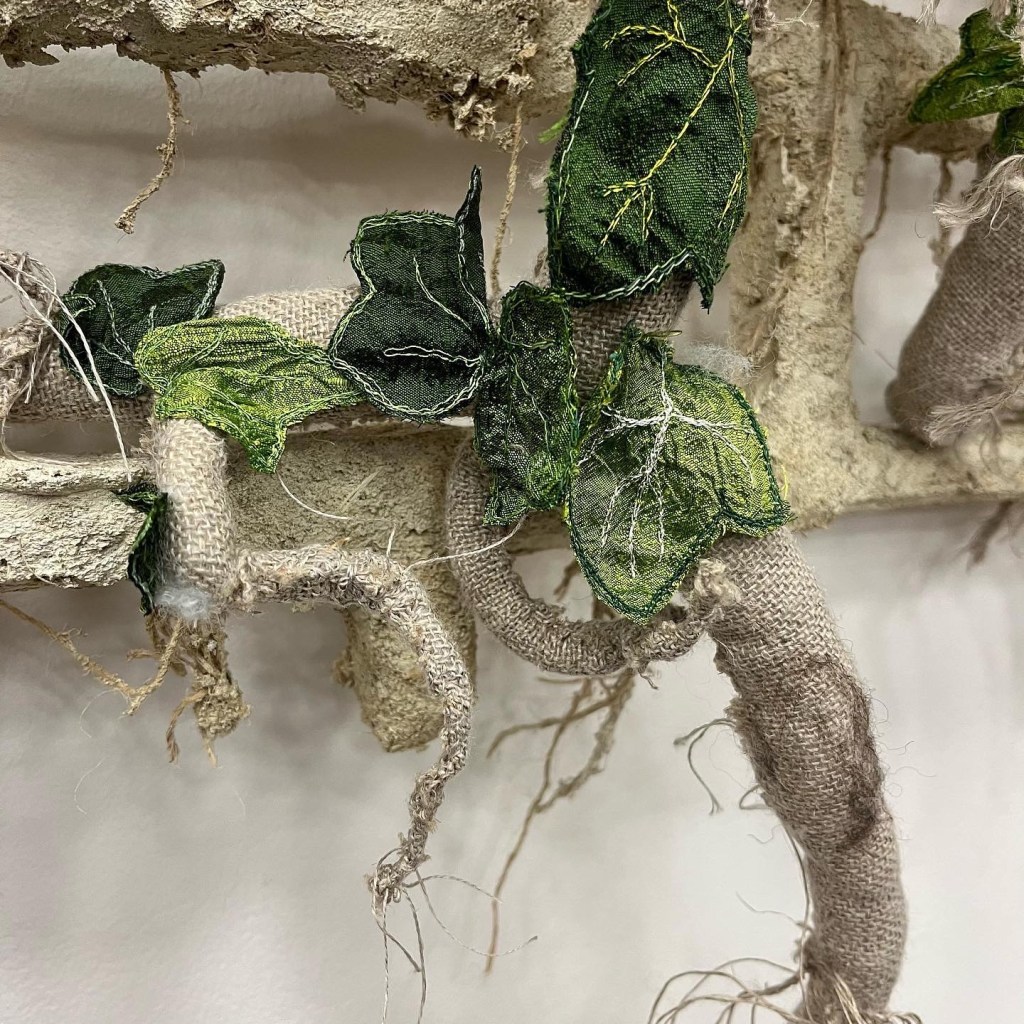

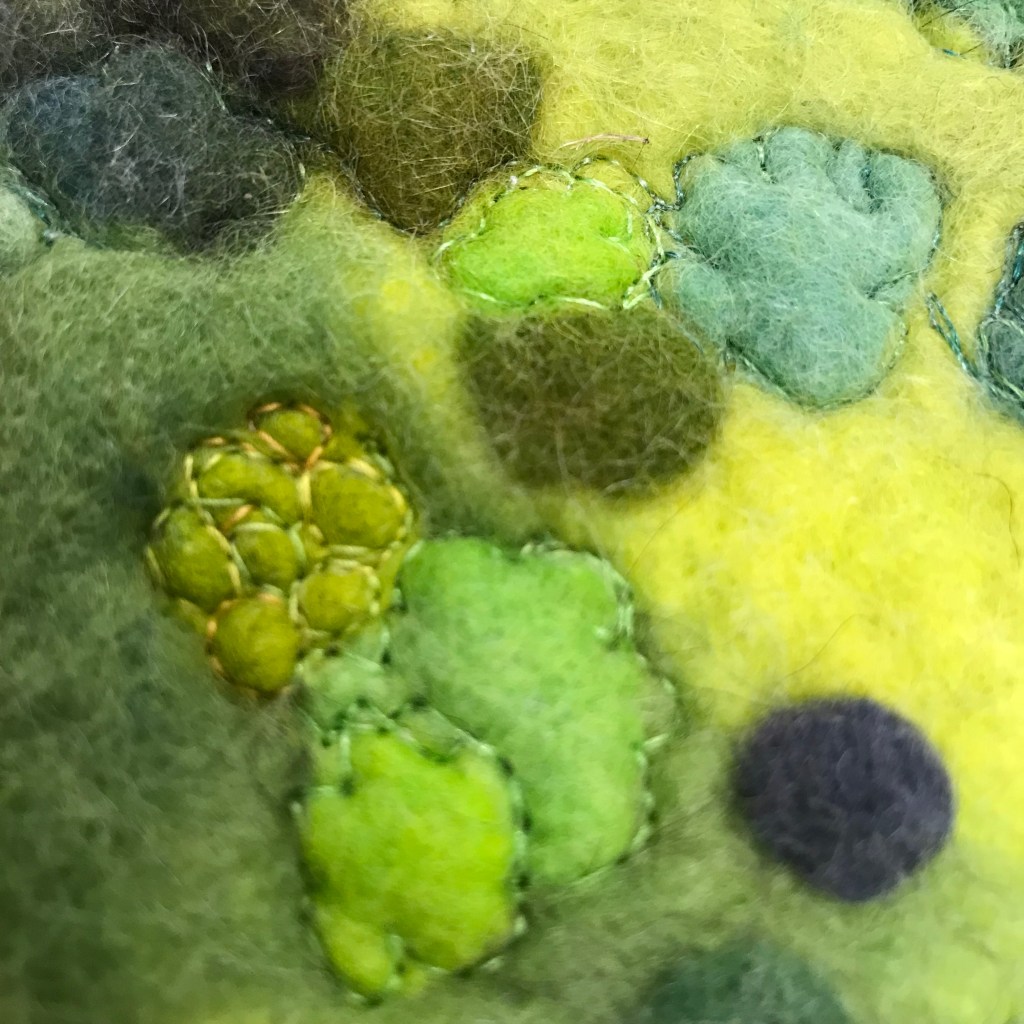

I started with the background. Three large woodland panels. To ensure similarity, I laid out designs for all 3 panels side by side and felted them simultaneously.

The nature of felting and (crucially here) the finished dimensions depend on a number of variables – type and amount of fibre, the number of layers, the direction of the fibres on each layer, the amount and temperature of water used at each stage, the type of soap, the duration and intensity of the agitation and rolling and the type of fulling method used. It was vital to me that the three panels looked similar but also that they shrank to the same size. For that reason, I treated the felting as one large piece rather than 3 smaller panels.

Once I had felted the backgrounds it was time for some free motion embroidery and then handstitch. I usually leave handstich for times when I’m tired and can enjoy sitting and thinking while I stitch. Hundreds of little bluebell heads and lots of contemplation!

I wasn’t sure how to create the wall layer. My initial idea was to produce a calico wall with painted stones and to stitch it together like a mattress. The resulting sample lacked the glint of the sandstone, so the next thought was to use organza and stitch.

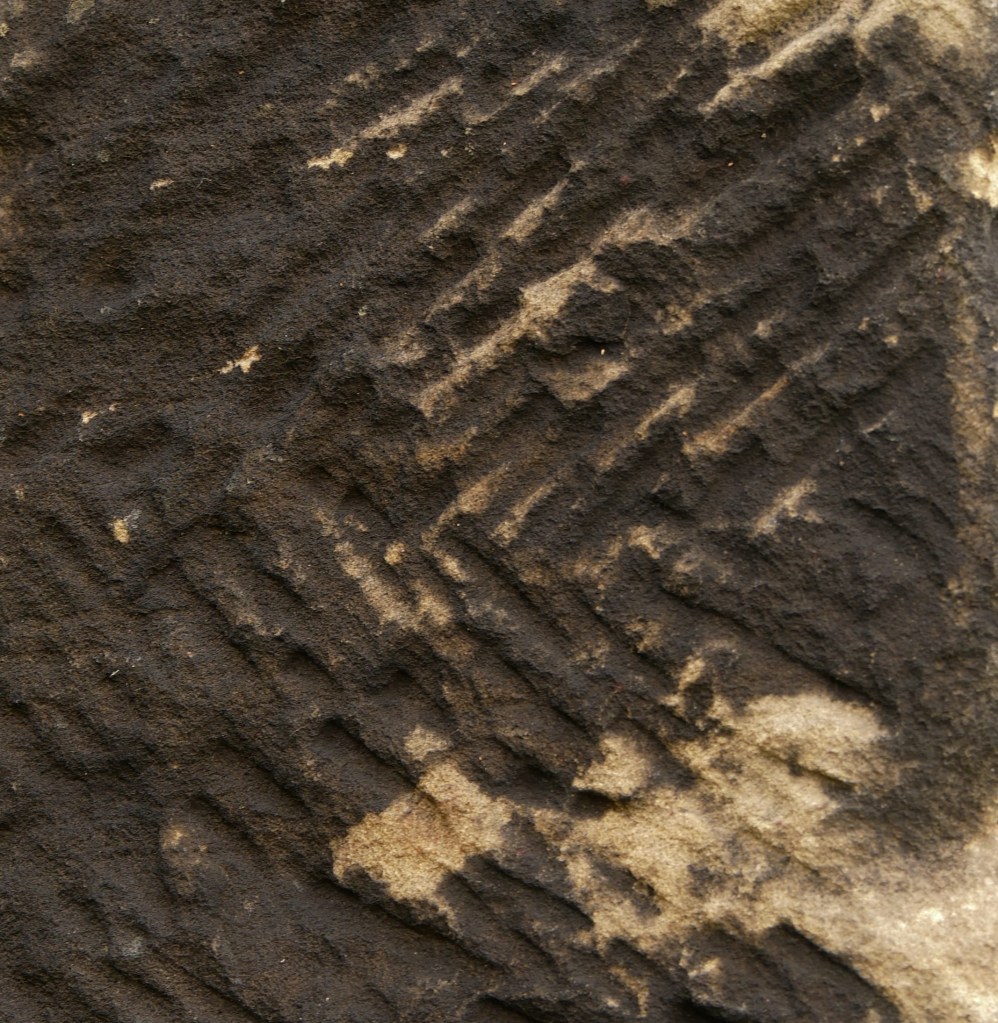

That gave me shine but I started thinking about how to construct the pictures and realised that something more rigid than a stuffed mattress would be easier to hold in place than something soft and flexible. I also had a chat with the brilliant John the Framer (Saturday mornings, Pontefract Market, outside, opposite the entrance to the covered market hall – I cannot recommend him enough!) which gave me more insights into how I could achieve the effect I wanted. Just then, in a wonderful moment of synchronicity, a friend de-stashed some foamboard in my direction and that gave a perfect solution, lightweight, easy to cut in complex shapes, rigid. So, the final construction of the wall is hand dyed felt, covered in layers of organza fragments, painstakingly stitched in free-motion embroidery so the same patterns on the stones reoccur across the three panels.

This was then cut out, used a template for the foamboard and finally stitched together by hand.

For some reason I miscalculated the amount I needed for the side gusset so am left with metres of it. Keep an eye out for it in future projects!

The foreground was easy in comparison. A thick layer of handmade felt for the grasses and sticky-burr plants and brambles, not forgetting the stinging nettles which love this site. As often happens with a piece of work which takes time, I had fallen a little out of love with it, but the foreground somehow breathed life back in it for me.

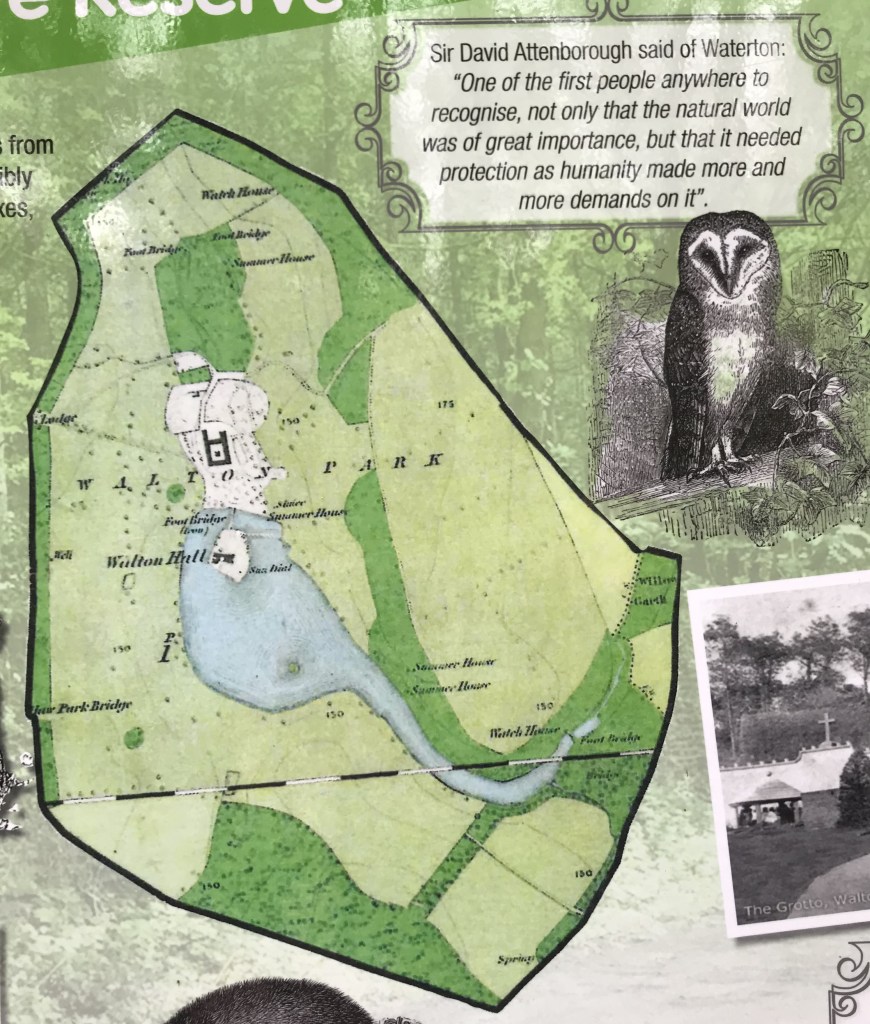

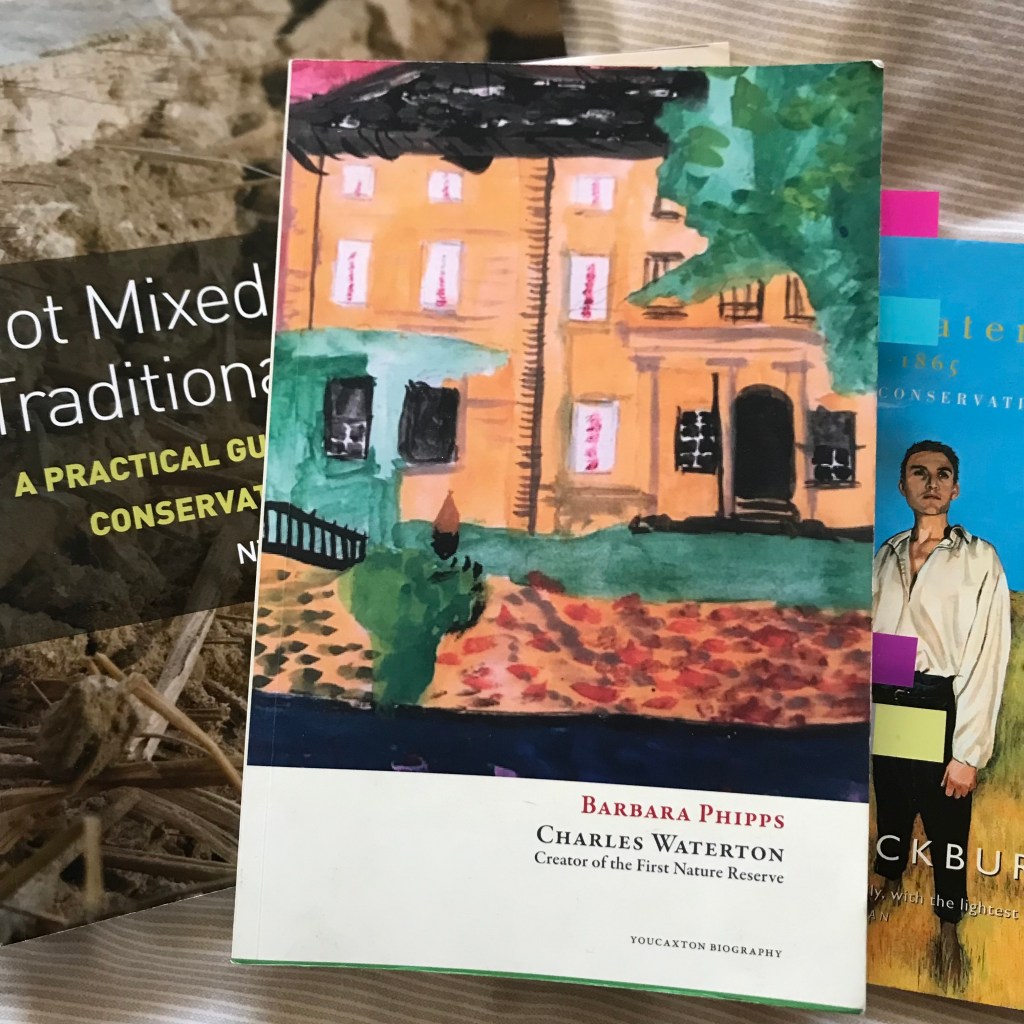

I also included a purple bramble stem in each piece – referencing the local legend that Waterton died while walking in the estate, from injuries sustained after tripping over a bramble. Watch your step!

The popularity of this spot raises more general questions about our attitudes to old structures like Waterton’s wall. Decay provides us with attractive and unexpected frames for the views we enjoy. The unfinished phrase “Now you see it” (now you don’t) of the title, refers to the wall’s decline. But it could also be seen as referencing what we can now see through the gap.

Indeed, the old structures themselves are far more interesting than a brand-new wall. So, what do we do? If we rebuild, we lose the character, of the wall we love, but retain its significance. If we do nothing the wall will continue to disappear. If we preserve what remains now, we can perhaps have the interest of age, but the certainty of a future.

The format for these three pieces is the same. A felted background of the wood at bluebell time. The foreground too, offers continuity—the wild undergrowth which grows and dies back each year. It is the mid-ground which changes. The wall, in decline from year to year. What would the fourth picture show?